Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. photo credit: smemon87

photo credit: smemon87

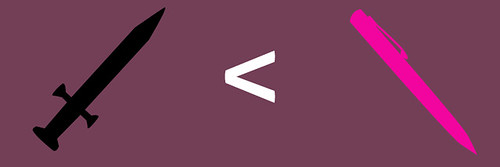

After reading violent threats against Frances Fox Piven online, my first thought was “If books are so powerful, then why threaten with a gun—go and write your own book.”

Hannah Arendt, in On Violence, describes violence as indicating the lack of power. Power, she says, is the capacity to capture people’s hearts and minds, to change the way they think and act. In the late 1960s, she wrote against what she saw as leftist writing that glorified violence (she cited Fanon and Sartre). Power is what separates Karl Marx’s ideas, which galvanized, inspired, and engaged debate, from Joseph Stalin’s regime of suppression through threat and through actual violence. (See also page 2 in her article in The New York Review of Books). Fascist regimes, according to Arendt, are regimes without new ideas (see her review of The Black Book in Commentary, page 294). What they have instead is a monopoly on the means of violence.

But, what is the written threat of violence? It is not the same. This week seemed like a good time to turn to Judith Butler’s scholarship on hate speech (Excitable Speech). I was surprised to find that Butler takes apart the distinction between physical violence and language, and two of the main terms she uses in this project are control and vulnerability. In society, people are vulnerable to and dependent upon language, and language is beyond our control. Therefore, hate speech is said be “like a slap in the face” because being called a demeaning name actually affects a person’s sense of their self and the way they appear to others.

Control—language is beyond the speaker’s control. Frances Fox Piven’s writing has been interpreted in ways she never intended, ways that seem irrational to her (and to me). Yet, Butler argues, engaging in language always means the speaker does not control the way her words will be interpreted. Others may not read the same material in the same context in which you wrote it. The speaker can suddenly find herself in a struggle she never intended to enter, one with terms and stakes she never predicted.

Even in the absence of real violence, does the written threat of violence prove Hannah Arendt’s point—does violence in language indicate a lack of power, and the lack of new ideas? If it does indicate a lack of power, how is one in the position of professor at City University, and other professors and authors, to respond? As Butler argued, it seems to me that suddenly authors are being unpredictably granted a power they have not themselves presumed to wield. Are they responsible to a power that anyone ascribes to them?

Graduate scholars are aware of how insular and hermetic our work and our communications can be. Now I’m wondering if scholars should be prepared to take their ideas out for a spin, outside the contexts of journals and conferences, to imagine interpretations from more diverse audiences and to defend and delineate their ideas. This hasn’t been part of my training—I’ve been trained to confront some scholarly authors with the oppositional arguments of other scholarly authors. As a writing and public speaking teacher, I coach students to consider their intended audience, to write towards their common knowledge and interests. Now I’m wondering how much writers and speakers need to consider their ability to respond to unintended interpretations, unintended audiences. It’s a frightening challenge, but Fox Piven seems to be responding steadily in what I can only imagine has felt like a very shaky playing field.